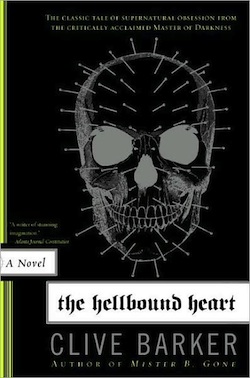

So many of the important horror novels of the eighties were big books, tomes like It and Dan Simmons’s 1989 novel Carrion Comfort. So, I thought, it might be nice to wrap up this eighties horror reread by giving you all something quick to consider for dessert, a book you might easily find time to reread yourselves. This line of thought is what brought me to Clive Barker’s quick and astringent The Hellbound Heart.

Coming in at a bantamweight 150 pages and change, The Hellbound Heart is the story of Frank, a jaded sensualist who has seen and done it all. Having lost interest in the workaday world of kink, he summons the strange and dangerous Cenobites, hoping they can help him discover otherworldly extremes of pleasure. Unfortunately, the Cenobite concept of fun doesn’t mesh at all with the human nervous system, and they’re definitely playing without a safe word… so instead of endless smutty fun, all Frank gets is a one-way ticket to eternal torment.

Now in a sense this is okay, because Frank is not all that nice a guy. He seduced his brother’s wife on the eve of their wedding, destroying whatever slim chance at happiness the two of them might have had. It’s no great tragedy when his quest for pleasure brings him to ruin. However, the house where he meets the Cenobites—and where a small sliver of his consciousness remains, trapped and forced to look out at the world he left behind—is co-owned by his brother Rory and his by-now miserable wife, Julia. After Frank disappears, the two of them move in.

Julia senses a presence in the house right away, and it doesn’t take her long to work out that it’s Frank. She’s been dreaming about him ever since their first encounter. With a little luck and a lot of obsessing, she comes up with a plan to free him. All she needs is a little blood to open the dimensional portal.

Okay, actually, a lot of blood.

The Hellbound Heart is an intense little book, a tightly locked chamber of story with only four characters: Frank, Julia, Rory, and Rory’s hapless friend Kirsty. It can be seen as yet another gender-reversed (though gorier than usual) retelling of Sleeping Beauty, with Julia as the handsome prince, seeking a reunion with Frank. Acting out of an unbearable weight of despair over her mistake in marrying Rory, she shows herself to be ruthless and undauntable.

Kirsty, meanwhile, emerges as a sort of marginalized heroine. Where Julia is gorgeous, charming and facile, Kirsty is plain, socially awkward, and has nothing but loyalty to recommend her to Rory, though she loves him desperately. Unappetizing though she may be, she’s smart enough to discern that Julia’s up to something—though she figures, at first, that it’s adultery. When she stumbles upon the horrific truth, she is forced to fight tooth and nail to survive.

In Julia and Kirsty we see another inversion of more traditional storytelling about women. Julia can be viewed as a sick version of a self-martyring nurturer type, willing to do anything for the sake of her beloved. Of course her beloved isn’t actually the guy she married, he’s pretty much doomed, and there’s nothing to admire in her ready bloodletting for Frank. Kirsty, on the other hand, is just running from the carnage. She’s no Ripley, out to save the crew, cats, and kids from becoming collatoral damage. Her fight only takes on heroic dimensions because the fate that awaits her is so very horrific.

There is often a lot of nobility and optimism to be found in horror fiction. It is a literature about terror, true, but in many of the great works of this genre, evil is balanced by the best qualities of its mortal opposition—by the good within whoever shows up to represent against the darkness. It is a literature that squarely faces human mortality. We all die, it reminds us, and nothing we do in the meantime to define ourselves can alter that fact. It’s a celebration of the idea of whistling in the dark.

What’s also true about horror fiction is that any given representative of the genre is usually going to have a few pockets of deep, hair-curling nastiness… where those good qualities of the heroic characters are momentarily overwhelmed by their frailties. You get those icky moments in other genres, of course—there’s a fair number of them in literary fiction, for example. But because horror’s very nature mandates that it examine the darkest recesses of the human soul, the incidence of those nasty moments seems, to me, a little higher.

I’m not necessarily talking about gore, understand. I’m talking more about incidents where human pettiness intersects with violence or cruelty in ways that are especially awful, where the only outlook is bleak. Where what is revealed isn’t altruism or courage or perseverance or even a morally gray quality like righteous revenge, but merely a slice of awfulness that makes one feel, however briefly, that our existence as a species might have no value at all.

In long horror novels, when this nastiness runs too deep, it overwhelms the other, laudable things. It’s too much to read at a hundreds-of-pages stretch. You then get those books that don’t necessarily succeed, that are deeply disturbing and don’t offer any emotional counterbalance. (Stephen King has spoken about being uncomfortable with the horrifically bleak outcome of Pet Sematary, for example, and the story goes he only submitted it for publication because his contract required it.)

Most of the horror novels I like do offer a thread of that nastiness, bundled within a whole bunch of other things. Even so, there are unremittingly nasty shorter pieces that do work… because, I suppose, they offer a smaller dose of bitter ichor. Michael Swanwick’s “The Dead,” is one of my favorites, as is Pat Cadigan’s “Roadside Rescue.”

The Hellbound Heart is a third.

It’s quick. It’s dirty. It’s a fundamentally mean story. Kirsty’s fight for self-preservation is laudable, but it’s a tiny victory, on the scale of a bug not creaming itself on someone’s windshield. This book is one of those artistic experiences that doesn’t leave you comfortable—you walk away wide awake, a bit disturbed, and grateful for whatever sanity or normality your life may hold.

It’s also thoroughly absorbing. As always, Clive Barker pulls you right into his characters’ minds and makes even the unimaginable seem like it might be lurking behind the nearest locked door.

A.M. Dellamonica has a short story up here on Tor.com—an urban fantasy about a baby werewolf, “The Cage” which made the Locus Recommended Reading List for 2010.

So I just went and did some research and found that this was the inspiration for the movie Hellraiser. Which makes me feel better because when I was reading this I kept on thinking, “I know I’ve seen a movie like this”. That was probably obvious for most people, but it’s been one of those days for me. Anyway, great write up on this book. I really want to go find it and read it now. I love it when I find out movies I like started life as a book first.

I really liked Barker’s stuff in the 80s and early 90s but haven’t kept up as much with his YA stuff (read the first one and it was okay). This one was good, I think it’s funny that one fairly short book turned into what, ten movies now?

I prefer his longer books though, like Imajica. His prose is excellent, very evocative without (usually) getting in the way of the story.

Old school Barker books are among my favorite books of all time. His ability to make the grotesque beautiful… Great and Secret Show is one of my top 10 books of all time.

I agree, Birdie–he really mixes the desirable and the foul in intriguing ways. Chuk, I agree that ten movies from one slender novel is amazing… but it’s all in the idea, right?

I love almost all of Barker’s stuff, and there is something truly special in Hellbound Heart. I like Abarat, his current YA series, but I yearn for another epic-length adult novel from him. Fingers crossed that Scarlet Gospels actually gets finished sometime in the (realitively) near future.

Well, my first ever encounter with anything of Clive Barker’s was watching Hellraiser – FWIW, I think he directed the first of the Hellraiser series.

And one of the things he managed to do that I’ve never ever encountered in any other horror film I’ve watched – he made it ambiguous. When the Cenobites drag Frank back with them at the end, I found it impossible to decide what he was screaming for – sheer terror, or frantic delight.

The book comes down on the side of the terror, of course – it’s not so easy to be so amiguous.

But Clive Barker made it possible to see the events from the Cenobites’ worldview, and appreciate it. Which reminds me of something my art teacher said one day when talking about modern artists – a critic had been looking at one of Francis Bacon’s paintings, and suddenly he had seen/felt himself in the painting. And it had scared him.

And that is a scary thing to do. It’s mystif-ish, even.

ISCOT – International Secret Conspiracy for the Oppression of Teddybears

ISCOT–wow. Now I want to close up my books and go look at Francis Bacon paintings.

Oddball that I am, one lingering question after reading this novella is, what happened to frank as he grew up to turn him into such a hedonistic sociopath? He was portrayed as an affectionate little kid. Puberty? Damn.